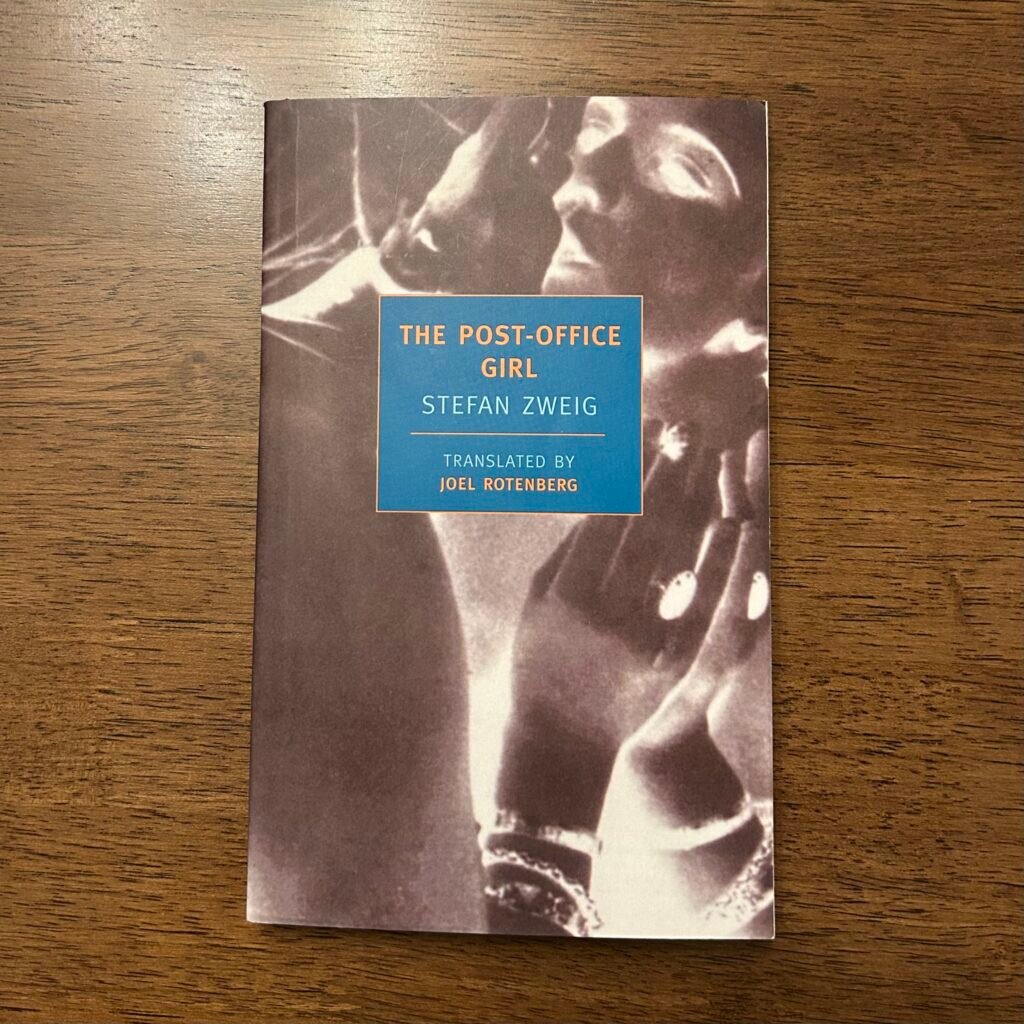

First published 40 years after the author’s death, Zweig novel provides biting commentary on the after effects of the First World War and on the psychological effects of poverty.

“The Post-Office Girl” follows Christine, who lives in near total poverty in order to support her sick mother on a small salary from a provincial post-office in Austria. While she had grown up somewhat comfortably in a merchant household, business had dried up during the war and inflation had left their savings nearly worthless. She feels her formative years (late teens and early twenties) were ruined by the war and its aftereffects which has left her lonely and nearing 30.

Things change when a telegram arrives from her American aunt who is visiting Europe and invites her to a short vacation at a hotel in the Swiss Alps. Her first vacation, Christine is apprehensive but agrees to the trip. Upon arriving, she is immediately self-conscious about her poverty compared to the other guests. Her aunt quickly buys her clothes, makeup, and a haircut to hide these effects. Christine quickly gains confidence as she is accepted into this world and sought after by several bachelors. She does as much as possible and enjoys herself greatly until cracks begin appearing in her persona. Fearing having her own past exposed, her aunt sends her back to her post early.

Back in Austria, Christine becomes bitter about her situation. Needing a short escape, she visits her sister is Vienna where she meets a friend of her husband, Ferdinand. He had fought in the war and been taken as prisoner into Siberia. After the war he was unable to get a footing and had been scraping by working odd-jobs and assisting an architect. They fall in love (or pity, or “trauma-bond”) feeling like they have finally found someone who understands the humiliating conditions that they are forced to endure. The two realize that a few moments of bliss won’t be enough to overcome their situation and begin plotting ways out.

Zweig’s posthumous novel certainly feels a little unfinished here. The first part (until Christine leaves Switzerland) feels complete and is brilliantly written. The second part feels rushed and a bit crudely written at times. The ending was not my favorite. Where Zweig excels, which is apparently in the first part, is in his ability to write very narrative-driven works that still manage complex psychological insight. Where other authors often manage this through long internal-monologue, Zweig is able to capture huge shifts in feeling through subtle shifts in tone and dialogue. At one point, I considered a novel great if it could provide a great story on the surface while also having plenty to pick apart below the surface–this and Mann’s Buddenbrooks are prime examples.

Zweig describes the humiliation of poverty in a way that feels both quite true and is quite sad to read. The reader feels for Christine as she encounters wealth beyond her imagination while wearing her best shabby clothes. Her anger is justified by her suffering through the war years thinking that everyone else was in a similar situation. Christine and Ferdinand both feel as though the life they wanted had escaped them as they struggled for so long just to eat. And to get ahead all they would need would be one of her uncle’s poker bets.

Leave a Reply